I'm scared of flying.

I know the numbers. I know I'm far more likely to whatever while whatevering. But fear isn't usually rational.

I don't like multiplayer games, either. I like stressful games even less, and I rarely have time for deep games that involve deep time commitments.

Yet I still find myself sitting on a plane, clutching the arm rests and regulating my breathing. I'm on my way to do volunteer work for SpyParty, a game that is all the things I just described. I'm taking the kind of trip I never take, to support the kind of game I never play.

If you're the type of person who reads articles like this (and it appears that you are), you probably already know about SpyParty. You know that it's an asymmetric multiplayer game where one player is trying to blend in with AI-controlled guests at a fancy cocktail party and the other is a Sniper watching the party from the outside with one bullet, trying to figure out which partygoer to lodge it in.

You're probably also familiar with the Penny Arcade Expo (PAX), an annual convention in Seattle where video game creators and studios display their products for tens of thousands of gamers.

What you may not know is that SpyParty has been among the exhibitors at PAX for six consecutive years, and that PAX is where the game's dedicated community shines the brightest. Each year the top players in the world instinctively fly north at the end of the summer, like confused geese, to volunteer at developer Chris Hecker's modest booth.

The volunteers are partially lured by the handful of free exhibitor badges provided in exchange for their help, but more by their desire to evangelize for a game unlike any other. Nearly all of them have robust gaming experience and are not easily impressed, but this game of bite-sized espionage is too strange and refreshing to merely enjoy: it has to be shared. Not many people play without preaching, and when the preaching is this passionate, it wins a lot of converts.

The passion is a bonus, but the real reason they're here is pragmatic: SpyParty is complicated. Like, really complicated. I used the word "preaching" purposely, because even a thin description of the gameplay sounds borderline catechismic. Over the next four days, the players working the booth will recite, refine, and repeat their own versions of the same sales pitch, trying to convince each conventiongoer that this game really is different. Because it is.

The first time I played SpyParty, I was a nervous wreck. Though it's immediately engaging and challenging, it's not especially pleasant for beginners. As Spy you feel clumsy and obvious. As Sniper you feel overwhelmed. It can be hundreds of games before you notice these fears are mutually exclusive, and thousands more before you really internalize it.

Stressful as it is, there are a few things compelling you to keep playing. For one, it's short: the average game is about three minutes long. It's also deep: each game is a combination of high-level strategy and low-level execution (in more ways than one, if you fail). This means there are always dozens of things you could've done better, giving the game an addictive quality. While playtesting an early build, game design demigod Will Wright (SimCity, The Sims) remarked that it had "that potato chip thing"—you always want just one more.

What hooked me was that the game required my full attention. A truly engrossing game has a way of ghosting its mechanics onto your mind long after you stop playing. A couple of weeks after joining the beta, I was driving to work and I noticed a police car sitting by the side of the road. The sensation of being watched, and the tiny spike of stress that resulted, instantly brought to mind the sensation of the sniper's laser burning into my character's head. It was then that I realized how quickly this game had burrowed into my consciousness. It was then that I realized: you never really stop playing.

From Seattle With Love

As soon as my plane lands I turn my phone on, and texts start rolling in from other players. A few of them are already in town, and a few more are coming in that evening. Everyone's excited; the first night is the only one we'll all be together and free from any booth duties, so everyone's anxious to congregate and do something fun.

As I approach the hotel my phone vibrates. It's Dennis (known in-game as "virifaux"), who has the most games of any player. "I just saw you walk by," he says, and when I turn a corner, four of the best players in the world come strolling out of the building. I've never met any of them but they're all old friends. "Old," in this case, is relative to the medium: I'm the only person in the group whose age doesn't start with a two.

There's good reason to be excited, because we can all say and joke about things that maybe a dozen people in the world can appreciate, and a third of those people are now in the same room. The conversation is awash with inside jokes, obscure references, and opaque game-related shorthand to the point where anyone eavesdropping would think we were actual spies, speaking in code.

We talk so animatedly that the hotel manager asks us to keep it down. Instead we head out into the city in search of a place to eat with enough background noise to allow us to continue talking loudly. We cram as much revelry as we can into the evening, knowing how tired we'll be in the evenings to come. Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we Spy.

Debug Another Day

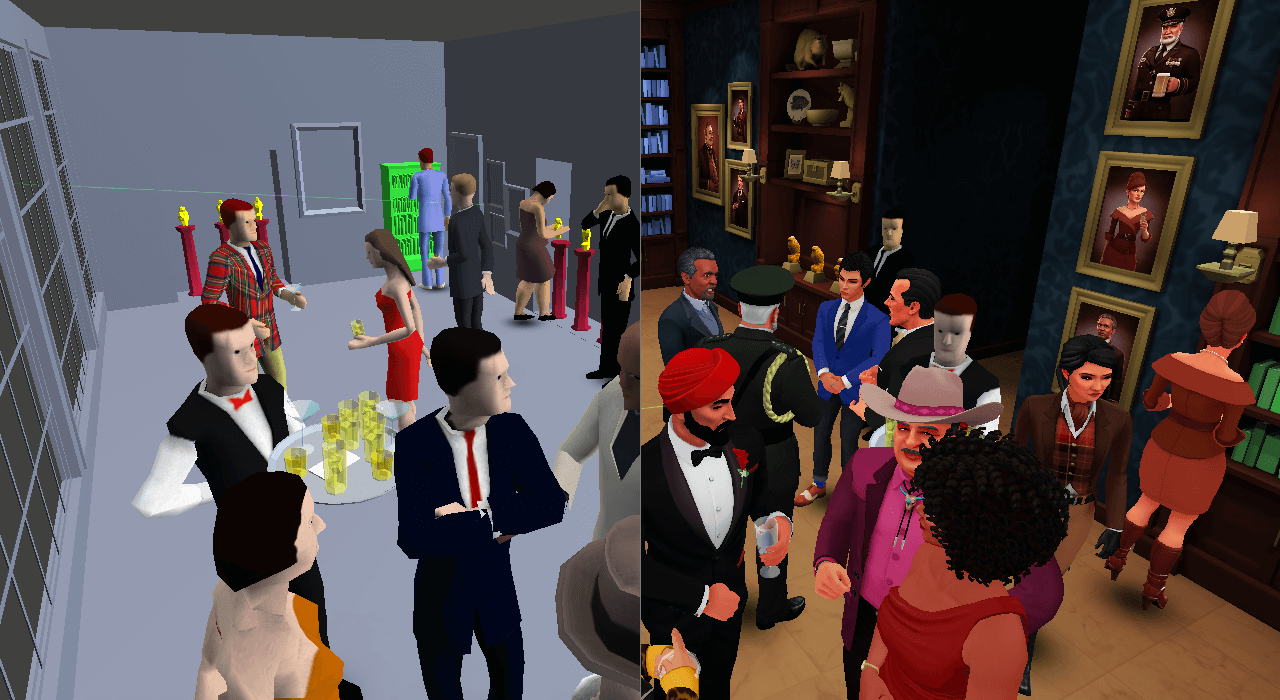

The moment we enter the convention center the next morning there's work to be done. Hecker tells us he's "coming in a little hot" having updated the game's build as recently as the night before, an unplanned annual tradition. In this update, he's taken the game's first map ("Ballroom") and upgraded it from the old placeholder art, to the game's sleek new style. This is the first time any of us are getting to play it, but there's no time to admire the view, because we've been tasked with destroying it.

The new build contains significant changes, and significant changes mean bugs. Normally, you deal with bugs through testing and time, but we only have one of those things. With just 15 minutes to go before the convention opens to the public, I and four other volunteers are sitting in front of monitors, running through as many missions with as many characters as we can, trying desperately to break things.

When testing for bugs, it's not clear when you're supposed to be happy. On one hand, finding a bug is bad: it means something is broken. On the other hand, you already suspected something was broken, and getting confirmation (and detailing the problem) is a relief. Whatever emotional reaction is appropriate, it isn't long before one of the testers finds a problem: the "Inspect Statues" mission isn't working.

Normally, a broken mission would be the worst possible news; it isn't something that can explained away or glossed over during demonstrations, which means Hecker would likely have no choice but to update the build right then and there, leaving the game unplayable just as the convention opened. Mercifully, the broken mission isn't one of the four featured in the demonstration process, so none of the new players will encounter it. Nevertheless, it's fixed by the next morning.

Selling Licenses to Kill

The floor of PAX resembles nothing so much as an old-timey carnival, and the exhibitors are the carnival barkers. They build eye-catching displays and then stand outside them, eager to explain to passers-by why they should stop and step inside the metaphorical tent. Only their wares aren't cure-all tonics or vim-and-vigor elixirs, but software.

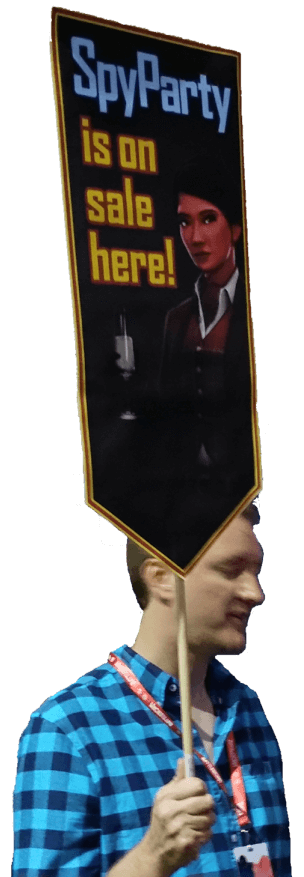

In our case, we literally have someone ("krazycaley") standing out front in a blazer with a cane; the only thing missing is a straw hat. Neither the blazer nor the cane are an affectation, though you could be forgiven for thinking they were given how well they fit the game's upscale theme. The clothes, the cane, and the man all say the same thing: this isn't your typical video game.

The size and location of the booth say it, too: we're in the corner of the third floor next to a glass-encased firehose, surrounded by styrofoam castles and various Minecraft stagecraft. We're fifteen feet from an area literally called "The Behemoth." You'd think this was a problem, but the juxtaposition between these massive displays and our tiny rectangle—which is half a dozen monitors, some banners, and a few folding chairs—creates a sort of marketing jujitsu that piques people's interest. SpyParty projects otherness, and the kinds of people likely to be interested in that otherness can sense it immediately.

Our resident rabologist likes to tell the story of how he explained the premise to a man who, upon hearing it, pulled a $20 bill from his pocket, held it dramatically over his head, and marched over to the end of the booth to purchase the game sight unseen. I end up experiencing something similar myself: on several occasions, people in line say some version of "I don't have time to play this right now. Can I just buy it?"

Those that stay end up waiting a bit, because each pair of players takes close to 15 minutes: several minutes each for a hands-on tutorial, and then one game in each role. Anything less would render the demo too confusing and frustrating to be worthwhile.

The tutorial is the only part we can control the speed of, so streamlining it is key. That's pretty difficult, because there's a lot to cover and most of it resists summarization. The first couple times I explain the game, I'm clumsy about it. Each person I talk to understands, but I take too long and have to double back after forgetting to mention salient details. Thankfully, after just a few iterations, the spiel is much improved.

The process is a mix of salesmanship and stand-up comedy: you explain things and see how people react. You keep your eyes on their faces and watch for looks of recognition and hints of smiles. You keep using what works and discard what doesn't, and through sheer repetition you build your routine and refine your patter.

If I finish my run-through a little quicker than the volunteer on the other side, I use the extra time to touch on basic strategy and psychology. "You're never as obvious to the Sniper as you think you are," I tell them. Fear isn't usually rational.

You go through this again and again, honing and polishing as an array of different people sit next to you, each reacting in subtly different ways. And as you do, a pattern emerges. Or, more accurately, the lack of a pattern.

Live and Let Spy

It's impossible to work the SpyParty booth and not be struck by the sheer size of the untapped gaming market. The game disproportionately catches the eyes of the disproportionately underrepresented. Women are already more prevalent on the convention floor than they typically are in online multiplayer games, and they seem more prevalent at our booth than they are on the convention floor.

The community is, for the moment, less diverse than the cast of characters. It's not surprising that the game its creator likes to describe as a "reverse Turing test" has attracted largely young, tech-savvy people who like exploring the minutiae of arbitrary systems, nor that most of the people who fit this description are twentysomething males with a background in IT. But these are the early adopters of what's still a highly inaccessible game; what's exciting about SpyParty is that it has the ability to appeal to everyone else.

Whether this fact will have you nodding your head or shaking your fist, in the aggregate, the people I train at PAX tend towards their corresponding stereotypes. The players who pick up the control scheme the quickest are mostly adolescent men, but they're also the ones I have to repeat instructions to the most often. Conversely, the women I trained were usually less comfortable with the controls, but much better at absorbing the instructions. On net, the women made better decisions, but the men executed their decisions more efficiently. What's important about this is not that the approaches were different, but that both approaches allowed the player to be competitive.

It occurs to me that this what a great game ought to be able to do: allow people to approach the game with whatever angle feels natural to them, and still compete with someone coming from an entirely different angle. The fundamental flaw in most games comes from the mere fact that they must be mastered; you must adapt yourself to fit the game's constraints. This alone means most games will mostly attract a certain kind of person: the kind that finds it appealing to learn and master a set of invented rules, to explore and exploit constructed systems.

This isn't usually seen as a problem, because the sheer number and variety of available games ensures that everyone can find something that suits them: there are games that let you shoot aliens and games that let you control flower petals with the wind. But games are the rare art form (yeah, I said it) that can function as a universal language, like music, trade, or mathematics. And when you think about games in this way, you realize it flips the entire market on its head: what if, instead of making a million games so each person can find one, we had one game that accommodated a million different kinds of people?

By this measure, the perfect game would be one which took your existing abilities and tendencies, whatever they were, and translated them into some common performance currency. A game that could do this would split the atomization of the existing market. It would allow wildly different people to compete in the same arena.

SpyParty hasn't fulfilled this Grand Unified Theory of gaming, but it's one of the only games that's even noticed the opportunity. And its translation of skill, and the innate inclusiveness that comes from meeting people where they are, has formed the basis of an exceptional community.

You Only Go Twice

Games and their communities are usually treated as separate entities, but with SpyParty they're inseparable. In a purely technical sense, there's no real single player mode. To play SpyParty is to play with someone else, so there's no way to, with apologies for bastardizing Yeats, distinguish the gamer from the game. Such a game will necessarily live or die with the quality of its community.

If PAX is any indication, it seems more likely to live. SpyParty players make this PvP pilgrimage to essentially replicate themselves: they're trying to create as many new players as possible, preferably ones that become dedicated enough to make the same trek and eventually do the same thing, starting the cycle anew. If not for the flat panel monitors and cosplay, you could be forgiven for confusing it for a nature documentary.

Just a few players are awarded exhibitor badges each year, and there's an unofficial policy of rotating new people in every couple of years. Two veterans come back to teach two new volunteers, who often go again as veterans themselves the next year, and so on. This year, the rotation has lined up just right, producing the single largest gathering of elite SpyParty players ever. In attendance will be the top four players, seven of the top 10, and nine of the top 20. All told, the cumulative experience is over 100,000 games. Or, measured in relation to the booth's tiny sliver of floor space, over 1,000 games per square foot.

That SpyParty players go to so much trouble just for admission to the convention (which they're too busy with the booth to explore much anyway) is remarkable, but more impressive is how many pitch in without having any obligation to do so. SpyParty players are, as I mentioned earlier, usually gaming aficionados, so many of them attend PAX as normal conventiongoers. But even though hundreds of games they've never played are vying for their attention—and they have a limited amount of time to take them in—nearly all of these players help out at the booth, some for hours at a time. It's the equivalent of working for free, on your day off, at a job you don't even have in the first place. If you didn't know better, you'd think these were Deadheads following Jerry and Bob around.

This isn't prohibitive for most of the community, because a great many of the elite players already live on the West Coast (California, in particular, is relatively dense with SpyParty enthusiasts). But there are several major exceptions: I'm flying in from Pittsburgh, you can probably guess where "canadianbacon" hails from, and Stuart ("sharper") is upstaging everybody by coming all the way from Australia.

But there are other hurdles, even for those nearby: one of the players pitching in on their own time this year is Taylor Shuss ("drawnonward"), who has the second-highest number of games played in the world. Shuss was selected for an exhibitor badge the last two years, but missed the cut in 2015 due to a higher-than-usual number of applications from top players. Adding the cost of convention tickets to the normal costs of travel and lodging put the trip out of his budget.

Shuss, who is famous in the game's community for having streamed thousands of his games, decided to enlist the help of other players by holding a telethon of sorts. Privately, he confided to friends that his expectations were modest (though the community is devoted, it's still small) and that if he could raise the cost of the badges—about $200—he'd be able to make it work. He hit that goal in the first 30 minutes, and by the end of the day he'd raised $600, the cost of the entire trip.

"I expected to get a few bucks here and there. I was just flabbergasted at the result," he says. "I am not an emotional guy, so I know the stream probably didn't capture my feelings, but several of my close friends who were helping with the event said they had never seen me that way."

Active people are often referred to as being "a blur." This is usually hyperbole, but in Chris Hecker's case, it's literal: as I peruse the photos I've taken of the SpyParty booth, I find he's gesticulating so often and so fervently that he's fuzzy in nearly all of them. You're more likely to snap a clear photograph of Bigfoot than of Hecker when he's talking about his game.

To be fair, there's a lot to talk about: the game was first displayed publicly six years ago, and invitations to a closed beta (it's now an open beta) began going out over four years ago. This is possible because costs are low—Hecker is programming the entire game himself—but even a low burn rate has its extinguishing point. Hecker was quite candid in his 2014 Indiecade talk about the amount of money he's invested in the project, and the more time is spent improving it, the higher the expectations for the finished product. It's a high stakes bet on a highbrow, high concept game.

a highbrow, high concept game.

This being the Internet, some comment that the game will never see a formal release is quick to follow any blog post or news article about its development, but it's telling that these warnings come exclusively from people outside the community. Those who follow the game's development closely note a stream of new characters, maps, and the kinds of fine-tuning crucial to supporting high-level play. The game's development has been protracted, but purposeful.

If anything, the updates are coming too fast for the game's user interface: Hecker first introduced the playable new art characters and a corresponding new art map at PAX in 2013. It was added (like this update) so close to the event that it had been essentially untested, so he displayed the words "VERY EARLY WORK IN PROGRESS!!!" in red at the top of the screen. The message is still there in this year's PAX build. Midway through the convention, Korey ("kcmmmmm") jokes that "we can probably remove at least the first word."

For Their Eyes Only

I and the other volunteers eventually fall into informal schedules, rotating between roles as deftly as if we were transitioning from Spy to Sniper. After a couple of hours of tutoring, someone comes along and offers to relieve you, at which point you can take a quick break and explain the game to people passing by instead. The role rotation is usually accompanied by the distribution of cough drops, which after the first day take on a value roughly equal to cigarettes in penitentiaries.

Sometimes, an exhibitor badge ends up buried in a bag or otherwise temporarily misplaced, so one volunteer will borrow another's to get a drink or use the restroom. This leaves the person giving up the badge to try to look inconspicuous, to try to blend in with the crowds and look like they belong. I point out to the others that this is exactly what the game's been training us to do. You never really stop playing.

We even find ways to play while tutoring; like any group of people working together we find creative ways to fill time and adorn our activities, and the most natural way to entertain ourselves here is to imagine what we'd do in the player's place.

We can't actually perform missions or shoot each other, but the volunteer watching the Sniper's side can watch the characters and try to pick out the Spy, and then signal their guess to the volunteer sitting across from them. This has to be done in a way that won't cause the player sitting next to them to take notice. Korey comes up with a number of subtle expressions of body language to do this, like briefly rubbing his calf to indicate the character wearing knee-high boots, or placing his finger over his upper lip to indicate a character with a pencil thin mustache.

We try to one-up one another with increasingly abstract representations. My best is probably a slight cupped-hand wave, to indicate the character that looks like Queen Elizabeth. Korey's best is miming the act of holding a banner to indicate "Alice," a character based on artist John Cimino's girlfriend, who's standing about 15 feet away from us doing exactly that. She's holding a sign shaped like a medieval standard with a digital version of her own face on it.

Most of the characters are modeled after real people, either in appearance or mannerism, though the basis for each usually has a degree of celebrity. Only a couple are based on people you might actually meet, and Alice is one of them. This is surreal; it feels like I called a plumber and Super Mario knocked on my door. I've lost count of the number of times I've killed her, yet here she is, defiantly alive.

"This is so weird," I say when I introduce myself. "I've shot you hundreds of times. I feel like I should apologize." Thankfully, she doesn't seem to mind.

Today Never Dies

With just minutes to go on the final day, we're still trying to squeeze in as many tutoring sessions as possible. When the convention finally ends a voice comes over the loudspeaker, declaring "PAX 2015 is now over!" A half-jubilant, half-exhausted cry goes up from our fellow exhibitors. We join in, but our overtaxed throats don't contribute much to the din. Thirty seconds later we're already stacking chairs, rolling up wires, and carefully removing printed materials for use next year. The teardown/pack-up process takes about 45 minutes, and when we're done most of the booth fits into a couple of rolling bags. Such big ideas and ambitions, compressed into such a small space. You could hardly invent a better metaphor.

We haul the materials downstairs in a large freight elevator that feels uncannily like the ramp-up to an end-of-game boss fight. Instead, it takes us down to the garage, where we pack them into a car and say our goodbyes to Alice, John, and Chris.

But not to each other. Nobody quite wants the experience to end, and since our last night is as free of obligation as our first, we decide to do the same thing: walk around talking and searching for food. Eventually we travel up the top of a hill and find a restaurant with an outdoor section. We rearrange the furniture into one long table, facing the street, so we can observe the people going by. You never really stop playing.